Joachim Fest Histler Book Proud to Be German Again

Joachim Fest

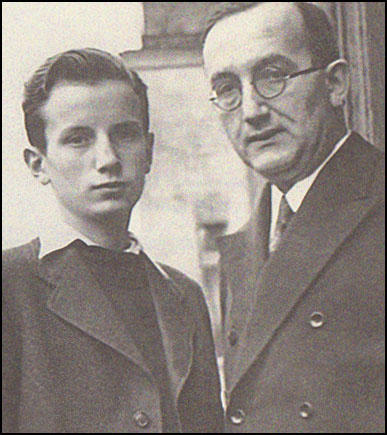

Joachim Clemens Fest, the son of Johannes Fest, a conservative Roman Catholic, was born in Karlshorst, near Berlin, on 8th December 1926. His begetter, the head teacher of the Twentieth Elementary School, was a strong opponent of Adolf Hitler and was outspoken critic of the Nazi Party. (1) In the 1920s he was a member of the Reichsbanner, a cross-party pressure grouping opposed to fascism. (2)

Neal Ascherson, has pointed out: "He (Johannes Fest) dominated his family unit, an imperious patriarch given to terrific rages at the dining-tabular array but unbending in his attachment to straightness, good behaviour and republic. His four principles were militant republicanism (he had detested the kaiser), Prussian virtue (taken with a spice of irony), the Catholic organized religion and German high civilization equally inherited by the educated center form." (3)

Soon afterward Hitler took power Fest "was twice summoned to the local education authority, and afterward to the ministry, and questioned on his attitude towards the Government." On his return from the third meeting he told his married woman, Elisabeth Straeter Fest, that he refused to back down and described the new government as a "rabble". She replied: "You lot know that I have always supported you lot in what you believe to be correct. I always will. But have you lot thought of the children and what your obstinacy could mean for them?" On 20th April, 1933, was suspended from his post. (4)

Rachel Seiffert has claimed: "From 1933 until the end of the war, this intelligent and energetic human being was reduced to an observer, watching the gradual erosion of civil society around him, first with incredulity and and so with horror. He full-bodied his efforts on his firsthand circle, urging Jewish friends to get out." (5)

The Politics of Johannes Fest

Johannes Fest had been a supporter of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) before information technology was banned by Hitler and was friends with several politicians including Max Fechner, a SDP activist, Franz Künstler, chairman of the Berlin SDP, Arthur Neidhardt, a senior officer of the Reichsbanner, and Heinrich Krone, a former member of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP). However, he was a strong opponent of Ernst Thalmann, the leader of the German Communist Political party (KPD).

Another friend was Dr. Goldschmidt, a Jewish lawyer. After the passing of the Nuremberg Laws Johannes Fest urged him to get out Germany: "Merely, Dr. Goldschmidt, who, as a High german patriot, had always felt it his duty to drinkable simply High german blood-red wine instead of the far superior French and to buy only High german wearing apparel, shoes, and groceries, had paid no heed. Frg, said Dr. Goldschmidt, was a state of police force; it was in people's bones, and then to speak." He later died in an extermination camp. (6)

In 1935 Joachim recalled hearing a row in which his female parent pleaded with his father to become a member of the Nazi Political party, arguing that a petty hypocrisy was justified to ease the hardship the family was undergoing. "Anybody else might join, merely non me... We are non little people in such matters." He used to quote the Latin maxim: "Even if others do - I do non!" Joachim later recalled seeing him come home covered in blood after fighting street battles with the Sturmabteilung (SA). (7)

The family unit could no longer afford servants and they all had to leave. The main loss was the nursemaid, Franziska, who according to Joachim was "after our female parent, she was the dearest person to u.s.a.". The children likewise had to make sacrifices: "There were no toys anymore and Wolfgang did not get his remote-controlled Mercedes Silver Arrow model racing automobile or I the football... The model railway already lacked gates, bridges, and points, so to make whatsoever progress at all we built hills out of papier-mache on which nosotros placed dwelling house-made houses, churches, and towers." (8)

There were several visits from the Gestapo. "The men in belted leather coats who came from time to time and with a Heil Hitler! entered the apartment without waiting to be invited were more than enough to create a threatening atmosphere. Without another discussion they shut themselves in the report with my father, while my mother stood in front of the coat recess, her face up rigid." (9)

In 1936 Joachim Fest became old enough to join the Hitler Youth. Nonetheless, his male parent refused to allow him to join the system. Despite this, Fest never joined any resistance grouping and did cypher active to damage the Nazi dictatorship, just refused to carelessness his Jewish friends until they were sent to concentration camps. (10)

In Feb, 1938, Adolf Hitler invited Kurt von Schuschnigg, the Austrian Chancellor, to meet him at the Berghof. Hitler demanded concessions for the Austrian Nazi Party. Schuschnigg refused and afterward resigning was replaced by Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the leader of the Austrian Nazi Party. On 13th March, Seyss-Inquart invited the German Army to occupy Austria and proclaimed wedlock with Germany. (11)

In his autobiography, Non I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006), Joachim Fest, pointed out that his male parent had mixed feelings most the Anschluss: "In March 1938... German language troops crossed the border into Austria under billowing flags and crowds lined the streets auspicious and throwing flowers. Sitting by the wireless we heard the shouted Heil!south, the songs and the rattle of the tanks, while the commentator talked about the craning necks of the celebrating women, some of whom even fainted. It was yet some other blow for the opponents of the regime, although my father, like Catholics in general, and the overwhelming majority of Germans and Austrians, thought in terms of a greater Deutschland, that is, of Frg and Austria as i nation. For a long time he sat with the family in front end of the big Saba radio, lost in thought, while in the background a Beethoven symphony played. Why does Hitler succeed in virtually everything? he pondered. Even so a feeling of satisfaction predominated, although once again he was indignant at the one-time victorious powers." (12)

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night)

Ernst vom Rath was murdered past Herschel Grynszpan, a young Jewish refugee in Paris on ninth Nov, 1938. At a coming together of Nazi Political party leaders that evening, Joseph Goebbels suggested that night there should be "spontaneous" anti-Jewish riots. (thirteen) Reinhard Heydrich sent urgent guidelines to all police headquarters suggesting how they could start these disturbances. He ordered the destruction of all Jewish places of worship in Germany. Heydrich also gave instructions that the constabulary should non interfere with demonstrations and surrounding buildings must not be damaged when burning synagogues. (14)

Joseph Goebbels wrote an commodity for the Völkischer Beobachter where he claimed that Kristallnacht (Crystal Night) was a spontaneous outbreak of feeling: "The outbreak of fury by the people on the night of Nov nine-x shows the patience of the High german people has now been exhausted. It was neither organized nor prepared but it bankrupt out spontaneously." (15) However, Erich Dressler, who had taken role in the riots, was disappointed by the lack of passion displayed that night: "One matter seriously perturbed me. All these measures had to be ordered from to a higher place. In that location was no sign of healthy indignation or rage amongst the boilerplate Germans. It is undoubtedly a commendable German virtue to go along ane's feelings under control and non but to hit out as one pleases; but where the guilt of the Jews for this cowardly murder was obvious and proved, the people might well have shown a little more spirit." (16)

Johannes Fest visited Berlin the following morning: "On November ix, 1938, the rulers of Germany organized what came to be known as Kristallnacht, and showed the world, every bit my father put it, after all the masquerades, their true face up. The side by side morning he went to the city center and later told united states about the devastation: burnt-out synagogues and smashed store windows, the broken drinking glass everywhere on the pavements, the paper diddled in the wind, and the scraps of textile and other rubbish in the streets. After that he called a number of friends and advised them to get out as soon as possible." (17)

Joachim Fest afterward pointed out that Kristallnacht had an touch on Jewish children at his school: "It was at this time that, without discover, the but Jewish pupil in our class stopped coming. He was repose, almost introverted, and usually stood a little bated from the rest, but I sometimes asked myself whether he ever appeared and so unfriendly because he feared beingness rejected by his schoolmates. We were still puzzling over his departure, which had occurred without a give-and-take of farewell... As a Jew he would soon not exist immune to become to school anyway. Now his family had the chance to emigrate to England. They didn't desire to miss the run a risk." (18)

Johannes Fest constantly felt guilty almost the crimes committed in Nazi Frg. His son rejected this idea: "Unlike the overwhelming majority of Germans, we were not part of some mass conversion… we were excluded from this psychodrama. Nosotros had the dubious advantage of remaining exactly who we had always been, and so of once again being the odd ones out." (nineteen)

In early 1939, Dr. Hartnack, the founder and director of a language school in Berlin, offered Johannes Fest a job. He had to use to the educational activity section for permission to take the post. After 3 weeks the authorities rejected his asking because of his previous refusal to join the Nazi Party. He was told that every bit shortly as there was evidence that the "petitioner had come around to a positive assessment of the National Socialist order and of its leader Adolf Hitler, so it would be prepared to review the matter." (xx)

Joachim Fest and the 2d Globe War

Joachim Fest attended Leibniz Gymnasium. In January 1941 he had used his pocketknife to carve out a caricature of Hitler on a school desk-bound. 1 of the boys who was a swell member of the Hitler Youth told his teacher nigh what he had done. "I denied any kind of political motive, but admitted the damage to property and asked to exist shown leniency." This was rejected and he was expelled from the school. Johannes Fest was told: "Information technology would be best if you took your other two sons (Winfried and Wolfgang) abroad at the same time!" (21)

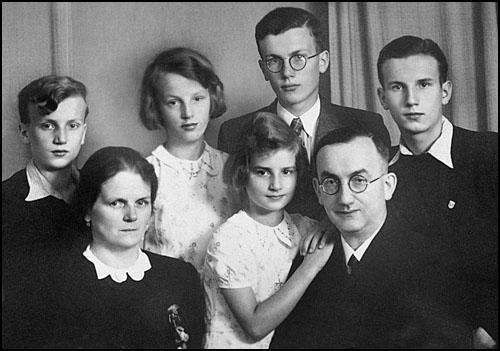

Front row: Elisabeth, Christa and Johannes Fest

In February 1941, Nazi Party officials arrived at the house and pointed out that none of his three sons had joined either the junior Jungvolk or the Hitler Youth. Johannes Fest sent them away: "Whoever yous are. I accept no intention of allowing you lot to come here, on a Sunday at that... Because we accept several times been pestered, likewise on a Sunday morning, by your lads. And then you haven't merely found out something. And now, will y'all leave my house? Leave! This infinitesimal!" His wife told him: "This time you lot've gone too far!" However, much to his surprise, they did not return. (22)

Joachim, Wolfgang and Winfried Fest were sent to a boarding school in Freiburg. Their new head teacher, Dr. Hermann insisted that they all joined the Hitler Youth. Joachim later admitted that he quite enjoyed the feel: "The bells rang out from Bernward's tower... and we listened reverently to the beating of a drum, a so-called Landsknechtstrommel which punctured not only the addresses given and the songs, but also the heroic passages of the war stories that were read out - we had to march around in a circle in the school playground in current of air and pelting, crawl on our stomachs, or hop over the terrain in a squatting position holding a spade or a co-operative in our out-stretched manus." He also was sent away to camp where he spent time on "mindless... military training drill." (23)

Joachim Fest received a bad report at the end of his time at the boarding schoolhouse. "Joachim Fest shows no intellectual interest and only turns his attending to subjects he finds easy. He does non similar to piece of work hard. His religious zipper leaves something to be desired. He is hard to deal with. He shows a precocious liking for naked women, which he hides backside a sense of taste for Italian painting. He displays a noticeable devotion to inexpensive popular literature; in the grade of an inspection of his work desk presently before he left, works by Beumelburg and Wiechert were establish... He is taciturn. All attempts by the rectorate to draw him into give-and-take were in vain. It is not impossible that Joachim will still detect the right path." (24)

In July 1944, Joachim Fest volunteered to join the German Army. His father objected to him joining "Hitler's criminal war". He replied that he did this to avoid beingness conscripted into the Waffen SS . (25) In October he was transferred to a small boondocks on the Lower Rhine: "At that place we were trained in duties as sappers, in building pontoons and in moving bridges." Soon afterwards he discovered this his brother Wolfgang had died while serving in Silesia. (26)

On 8th March, 1945, Fest was sent to Unkel in an attempt to stop the advancing American Ninth Tank Division. "At the edge of the forest we got the order to dig ii-man foxholes at intervals of ten yards. Now we were told that the American Ninth Tank Partitioning had captured the undamaged Ludendorff Bridge simply hours before and an armoured advance baby-sit had already crossed. Several attempts past the Germans to accident up the bridge or to smash the American units had failed." (27)

Historian of Nazi Frg

Fest was captured soon afterwards and was taken to a prison house camp in Attichy, France. Later on the war Fest studied history, sociology, German language literature, art history and law at Freiburg Academy, Frankfurt am Main University and Berlin University. He also became agile in the conservative Christian Democratic Union. His kickoff job was in radio, as in 1954 he became head of gimmicky history with the American endemic RIAS Berlin. (28)

Joachim Fest married Ingrid Ascher in 1959. Over the adjacent couple of years she gave birth to two sons. In 1961 he moved to goggle box as editor-in-chief of the German Norddeutscher Rundfunk. (29) Neal Ascherson has argued: " Fest was a handsome, restless, rather unhappy man. In postwar West Frg, he never fitted into any of the conventional slots. He had no time at all for Soviet socialism, which he considered an early variant of the virus that later on produced the Nazis, or for whatsoever Western class of Marxism. But although a correct-winger, he neither dreamed of reversing the upshot of the Second World State of war nor chose to imagine the Germans every bit helpless victims of a single madman: Hitler did not have to happen. No fe law of economic science or sociology wheeled him into history. Human beings – German language human beings – could accept stopped him, simply didn't." (xxx)

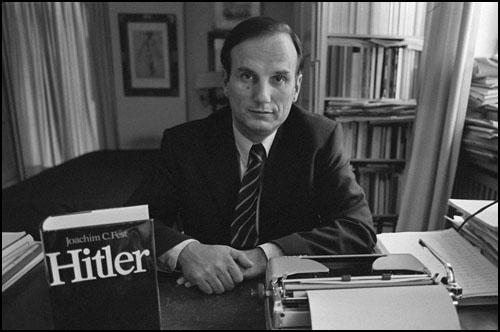

Joachim Fest's book, The Confront of the Third Reich was published in 1963. Jane Burgermeister has pointed out that "his profiles of prominent Nazis... a groundbreaking work for that time, could have come straight from the pages of Dostoevsky every bit Fest probes in scintillating style the dysfunctional psyches, personal ambitions, contradictions and self-serving delusions of the men who helped create the Tertiary Reich, while showing how they embodied the attitudes of their classes." (31)

The book immediately established his reputation as a historian. In 1966 he was approached past the publisher Wolf Jobst Siedler to assistance Albert Speer, then approaching the stop of his 20-year judgement at Spandau, in the writing of his memoirs. The result was Within the Third Reich, Speer's memoirs, which caused a sensation when it appeared in 1969. This was followed by Speer's Spandau: The Secret Diaries. In 1973 Fest published Hitler. It has been claimed that his biography of Adolf Hitler replaced the one produced by Alan Bullock (Hitler: A Study in Tyranny) as the standard work on the subject. (32)

Fest became co-editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the head of its culture section. In this post he argued tenaciously against the "singularity" of the Holocaust. (33) In June 1986 he created great controversy past publishing an commodity, The Past That Will Non Pass: A Speech That Could Be Written but Not Delivered, by young man historian, Ernst Nolte. He argued that information technology was necessary in his stance to draw a "line under the German past". Nolte complained that excessive nowadays-solar day involvement in the Nazi period had the effect of drawing "attention away from the pressing questions of the present - for example, the question of unborn life or the presence of genocide yesterday in Vietnam and today in Afghanistan".

Nolte so went on to hash out the Holocaust where he argued that information technology was not an exceptional event and could justly be compared to the crimes committed by Joseph Stalin: "Information technology is probable that many of these reports were exaggerated. It is certain that the White Terror likewise committed terrible deeds... Wasn't the Gulag Archipelago more than original than Auschwitz? Was the Bolshevik murder of an unabridged class not the logical and factual prius of the racial murder of National Socialism? Cannot Hitler's most clandestine deeds be explained past the fact that he had not forgotten the rat muzzle? Did Auschwitz in its root causes non originate in a by that would not pass?" (34)

Joachim Fest was attacked for comparing the crimes of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. He rejected this and claimed that the reason for this was the "left-wing mood" of the time. He was peculiarly critical of Günter Grass, the leading socialist writer of the time, who had attempted to deal meaningfully and critically with the Nazi experience: "When Günter Grass or whatsoever of the other countless self-accusers pointed to their own feelings of shame, they were not referring to any guilt on their own function - they felt themselves to be beyond reproach - but to the many reasons which anybody else had to exist ashamed. However, the mass of the population, so they said, was not prepared to admit their shame." (35) Fest's volume, Plotting Hitler's Death (1997) concentrated on the right-fly resistance to Hitler.

Joachim Fest came under attack from Gitta Sereny who accused him of protecting the reputation of Albert Speer when helping him write Inside the Third Reich. Sereny claimed in her book, Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth that Speer had lied about his knowledge of the Terminal Solution. Fest responded by produced his own biography Speer: The Final Verdict in 1999.

The book immediately established his reputation as a historian. In 1966 he was approached by the publisher Wolf Jobst Siedler to assistance Albert Speer, then approaching the end of his twenty-twelvemonth judgement at Spandau, in the writing of his memoirs. The result was Inside the Tertiary Reich, Speer's memoirs, which acquired a sensation when it appeared in 1969. This was followed by Speer's Spandau: The Secret Diaries. In 1973 Fest published Hitler. It has been claimed that his biography of Adolf Hitler replaced the one produced past Alan Bullock (Hitler: A Study in Tyranny) as the standard work on the subject. (36)

In 2006 Joachim Fest published his autobiography, Not I: Memoirs of a German language Childhood. The title was taken from his male parent'south saying, taken from the Matthew's gospel: "Others betray you, not I." The book concentrates of his family'due south reaction to living in Nazi Germany. "The family milieu is fascinating, and will exist unfamiliar to well-nigh British readers. Fest's parents were devout Catholics, proudly Prussian, and had been ardent supporters of the Weimar Commonwealth. Regarding both communists and Nazis with deep distrust, they kept company with like-minded political activists and intellectual Catholic clergy, and had many close Jewish friends... They lived with poverty, social exclusion, and under constant threat of visits from the Gestapo, simply Fest doesn't accept the moral high ground. If e'er a book demonstrated the slow but seemingly unstoppable reach of tyranny, even into the private realm, it is this one. He shows how tempting compromise becomes, even while information technology remains loathsome, and bears witness to the price and limits of individual courage." (37)

Joachim Fest died on 11th September, 2006.

Primary Sources

(one) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German language Babyhood (2006)

In March 1938... German language troops crossed the border into Republic of austria under billowing flags and crowds lined the streets cheering and throwing flowers. Sitting past the wireless nosotros heard the shouted Heil!s, the songs and the rattle of the tanks, while the commentator talked about the craning necks of the jubilant women, some of whom even fainted.It was yet another blow for the opponents of the regime, although my male parent, similar Catholics in general, and the overwhelming majority of Germans and Austrians, thought in terms of a greater Germany, that is, of Federal republic of germany and Austria equally one nation. For a long time he sabbatum with the family in front of the big Saba radio, lost in thought, while in the background a Beethoven symphony played. "Why does Hitler succeed in almost everything?" he pondered. Yet a feeling of satisfaction predominated, although over again he was indignant at the former victorious powers. When the Weimar Republic was obviously fighting for its survival, they had forbidden a mere customs matrimony with Austria and threatened war. Simply when faced with Hitler, the French forgot their "revenge obsession," and the British bowed so low before him that one could merely hope it was some other example of their "familiar deviousness." The Weimar Republic, at any charge per unit, would probably have survived if information technology had been granted a success like that of the Anschluss.

Nevertheless, my begetter connected, the union brought with it a hope that Deutschland would now become "more than Cosmic." Information technology was only a few days earlier he realized his mistake. Already at the meeting with his friends, which had been brought forrard, he learned of the persecution of the Jews in Austria, heard dumbfounded that he admired Egon Friedell, whose Cultural History of the Modern Age was ane of his favorite books, had jumped out of the window as he was most to exist arrested, and that in what was at present called the Ostmark there was an unprecedented rush to join the SS. "Why do these piece of cake victories of Hitler's never stop?" he asked one evening, later a pensive listing of events. And why, he asked on another occasion, was this mixture of arrogance and hankering for advantage breaking out in Germany, of all places? Why did the Nazi swindle not only collapse in the face of the laughter of the educated? Or of the ordinary people, who normally have more "graphic symbol"?

So in that location were always more occasions for that conspiratorial feeling that leap u.s.a. together; at least that'due south how my father interpreted the course of events. During the summer several members of my begetter'southward "undercover guild," as Wolfgang and I ironically chosen it, visited usa: Riesebrodt, Classe, and Fechner. Hans Hausdorf also came regularly again, and brought us children "presents to suck" and, as always, a pastry for my female parent. His heart-parted pilus was combed downwards flat and gleamed with pomade. Nosotros loved his puns and bad jokes. And, indeed, Hausdorf seemed to take nothing seriously. But once, later on, when we took him to task, his mood turned unexpectedly thoughtful. He said that homo coexistence really simply began with jokes; and the fact that the Nazis were unable to bear irony had fabricated clear to him from the start that the earth of bourgeois civility was in trouble.

(ii) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006)

On Nov nine, 1938, the rulers of Frg organized what came to be known every bit Kristallnacht, and showed the world, every bit my father put it, afterward all the masquerades, their true face. The next morning he went to the city center and afterward told us about the destruction: burnt-out synagogues and smashed shop windows, the broken glass everywhere on the pavements, the newspaper blown in the wind, and the scraps of cloth and other rubbish in the streets. After that he called a number of friends and advised them to get out equally soon as possible.

(3) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006)

It was at this time that, without find, the only Jewish pupil in our class stopped coming. He was serenity, almost introverted, and normally stood a little bated from the rest, but I sometimes asked myself whether he ever appeared then unfriendly because he feared being rejected past his schoolmates. Nosotros were still puzzling over his departure, which had occurred without a give-and-take of farewell, when one day, equally if past chance, he ran into me most the Silesian Station, and took the opportunity to take his leave personally, as he said. He had already done and so with a few other classmates, who had behaved "decently"; the residual he either hadn't known or they were Hitler Youth leaders, most of whom had as well been friendly to him, often "very friendly indeed," just he didn't see why he should say goodbye to them. As a Jew he would shortly not be allowed to go to schoolhouse anyway. Now his family had the chance to immigrate to England. They didn't want to miss the chance. "Compassion!" he said, as we parted, and he was already three or four steps away. "This time information technology is forever, unfortunately."

(4) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German language Childhood (2006)

One Sunday at the beginning of Feb 1941, soon subsequently we had come up back from church, 2 senior Hitler Youth officials entered the building, banging the street door and demanding to speak to my begetter. They had just found out-1 of them shouted from the bottom of the stairs-that none of his three sons had joined either the inferior Jungvolk or the Hitler Youth. At that place had to exist an end to it. "Malingering!" barked the other. "Impertinence! How dare you lot!" Everybody had duties. "Y'all, too!" the commencement ane joined in again.My begetter had, meanwhile, gone down to the pair. "Whoever you are," he responded, frowning in annoyance, "I have no intention of assuasive you to come here, on a Sunday at that, with a lie. Because nosotros have several times been pestered, likewise on a Lord's day morning, by your lads. So you haven't simply plant out something." And getting e'er louder, he finally roared at them, "You charge me of malingering and are yourself cowards!" And after a few more rebukes he shouted from the 2nd pace over their army-manner cropped heads, "And now, will you get out my house? Become out! This minute!" The pair seemed speechless at the tone my male parent dared to use, but earlier they could respond he drove them dorsum, so to speak, through the entrance lobby and out the door. The commotion had initially startled the whole building, and several tenants had appeared on the stairs. At the sight of the uniforms, however, they quietly closed the doors to their apartments.

Hardly had the street door closed backside the ii Hitler Youth leaders when my father raced up the stairs to at-home my mother. She was standing in the door equally if paralyzed and only said, "This fourth dimension you've gone likewise far!" My father put his arm around her and admitted he had forgotten himself for a moment. Simply first the Nazis had stolen his profession and his income, at present they were attacking his sons and Sun itself One had to show these people that in that location was a limit. "They know none," said my mother in an expressionless phonation. It was all the more important, objected my begetter, to signal it out to them.

(five) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006)

The bells rang out from Bernward's tower... and nosotros listened reverently to the beating of a pulsate, a so-called Landsknechtstrommel which punctured not only the addresses given and the songs, but too the heroic passages of the war stories that were read out - we had to march around in a circle in the school playground in wind and rain, clamber on our stomachs, or hop over the terrain in a squatting position holding a spade or a branch in our out-stretched manus...The duty at Haslach Camp was equally mindless equally all military training drill. We had to march up and downwardly the wide pebble paths between the sheds, throw ourselves onto the basis at a command, do rifle drill, put on footcloths, and, fourth dimension afterward time, perform the salutes as prescribed in regular army regulations "with a straight back". Furthermore, we were instructed in gunnery and ballistics, cleaning latrines, putting locker contents "in order" and fetching coffee.

(6) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

To be right when everybody else has been wrong can be a lonely, even disabling feel. This may exist a style of understanding the enigmatic character of Joachim Fest, the High german historian, journalist and editor who died six years ago. His Berlin family belonged to the Bildungsbürgertum - roughly, the well-educated center class - and rejected Hitler and National Socialism from the very first moment. They were non office of any resistance group; they did nothing 'active' to damage the Nazi dictatorship. They just refused to let this dirty, vulgar, evil thing across the threshold until, in the final stages of the war, it bankrupt in and took their sons and their father away to defend the collapsing Reich. For their defiance – refusing to join the Hitler Youth or League of German Maidens voluntarily, refusing to carelessness their Jewish friends until they 'disappeared' - the father lost his job as a headmaster and was banned from all employment. The family was repeatedly threatened by the Gestapo and denounced by its neighbours. They were lucky nothing worse happened to them.Fest was six when Hitler came to ability and an xviii-year-old pow when the Führer committed suicide. Much later, he was to become a historian, a maverick conservative of independent listen. He wrote 1 of the earliest postwar biographies of Hitler in German, and another of Albert Speer. In 1986, as cultural editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, he published the article by Ernst Nolte which was held to 'relativise the Jewish Holocaust' and touched off the Historikerstreit dispute over the uniqueness of Nazi law-breaking.

Fest was a handsome, restless, rather unhappy homo. In postwar Westward Germany, he never fitted into any of the conventional slots. He had no fourth dimension at all for Soviet socialism, which he considered an early variant of the virus that afterward produced the Nazis, or for any Western class of Marxism. But although a right-winger, he neither dreamed of reversing the event of the 2nd World War nor chose to imagine the Germans as helpless victims of a single madman: Hitler did not have to happen. No iron police force of economic science or folklore wheeled him into history. Human beings – German human being beings – could have stopped him, but didn't.

It was the matter of postwar guilt which isolated him. His family unit was exceptional because information technology had no reason to apologize for National Socialism, although his male parent, particularly, felt searing shame for his land. Fest conspicuously plant the cult of guilt unconvincing. If you looked more closely, he believed, you lot could see that the penitent was almost always blaming other people – his neighbours, his nation collectively – and never himself. At that place was a silent consensus non to stare into the bathroom mirror in the search for causes. The mood was rather: "Yes, we admit that Federal republic of germany nether that criminal authorities was guilty; at present permit'south motility on." But Fest, because he was genuinely not guilty, couldn't play this game. "Unlike the overwhelming majority of Germans, we were not part of some mass conversion … we were excluded from this psychodrama. We had the dubious advantage of remaining exactly who we had always been, then of once again being the odd ones out." So, too, did quite a few survivors of the sacrificial plots against Hitler. Anybody was respectful to them (unless they had been communists) and gave them medals. Only in the Bonn republic they were busy strangers, with a space around them.

Fest was born in Berlin, into a Catholic family. His grandfather had been the manager of the new housing scheme of Karlshorst, on the eastern border of the city, where the Fests settled. Just it's his father, Johannes Fest, headmaster of a primary school, who is in most ways the central figure of this book. He dominated his family, an imperious patriarch given to terrific rages at the dining-table but unbending in his attachment to straightness, good behaviour and democracy. His 4 principles were militant republicanism (he had detested the kaiser), Prussian virtue (taken with a spice of irony), the Catholic religion and German high civilization every bit inherited by the educated eye grade. He had been wounded in the First World War, and his patriotism was at once disquisitional and old-fashioned, costless of neo-infidel triumphalism and yet rooted in traditional stereotypes. When France roughshod in 1940, he remarked that "he was glad from the bottom of his heart at the French defeat, but could never be so at Hitler's triumph." This kind of ambiguity - yeah, simply if only someone other than Hitler had achieved it - paralysed would-be conspirators responses to the Czechoslovak crisis in 1938, the destruction of Poland and even the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. There weren't many like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who could cut the knot and hope for the defeat of their own country.

(vii) Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian (tenth Baronial, 2006)

Joachim Fest was the editor of Albert Speer's correspondence, as well as the author of an early on biography of Adolf Hitler and the definitive account of the last days of the Third Reich. But if his subject matter was challenging, then he had a personality to match. Not but a noted historian, he was a public intellectual of rigour, unrelenting in his pursuit of the upshot at paw.

During the bitter historians' dispute in the 80s about the Holocaust, referred to equally the Historikerstreit, Fest argued tenaciously against the "singularity" of the Holocaust; an iconoclastic position at the time, and still controversial – and painful – to many now. Co-publisher of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, one of Germany'south most respected broadsheets, Fest was a thorn in the side of the West German leftist intellectual orthodoxy before the fall of the Wall. His great value every bit a announcer was that he could cut through to the nub of a question, often with a cool, if cruel, wit. Take his response to Günter Grass'south Waffen SS membership, revealed 50 years after the fact. "I tin can't empathize how someone who for decades prepare himself up as a moral authority, and rather a smug one, could pull this off."

So the uncompromising Not Me of the title seems entirely in keeping with Fest's character. Really, it was his begetter's maxim, taken from the Matthew'due south gospel: "Others betray you, not I." Fest had an early on grounding in intransigence, and this is what makes this memoir so intriguing. It covers non his career, but rather his passage into machismo during the 3rd Reich.

The family milieu is fascinating, and will be unfamiliar to most British readers. Fest's parents were devout Catholics, proudly Prussian, and had been ardent supporters of the Weimar Republic. Regarding both communists and Nazis with deep distrust, they kept visitor with similar-minded political activists and intellectual Cosmic clergy, and had many close Jewish friends.

Great weight was given to learning in this circle, and Fest marks the stages of his formative years by the books he was given to read. At his boarding school in Freiburg, southern Deutschland, he buried himself in Schiller's Wallenstein "throughout the autumn and early winter of the Russian campaign, then that for me, Freiburg is forever associated with Schiller and equally an absurd contrast to the ice storms and blizzards exterior Moscow".

Immersed in both high culture and electric current events, the immature Fest was also taken seriously past the adults who passed through his household. This was obviously stimulating for a quick and developing heed, and mayhap also established the intellectual certainty that so marked him out in machismo. Afterward Fest made clear to his headmaster how parochial he thought him, his fellow pupils asked: "Have you lot no manners?" "I certainly did, I retorted, but only where at that place was mutual respect."

The author's bone-dry humour is axiomatic throughout the memoir. It emerges as just one of the many defences the family had to cultivate to endure the Nazi era. They lived with poverty, social exclusion, and nether constant threat of visits from the Gestapo, but Fest doesn't take the moral loftier ground. If always a book demonstrated the wearisome simply seemingly unstoppable reach of tyranny, even into the individual realm, information technology is this one. He shows how tempting compromise becomes, even while it remains loathsome, and bears witness to the price and limits of private courage.

His memories of his father are particularly affecting in this regard. Johannes Fest was a school teacher, whose repeated refusal to join the Nazi political party led to him being banned from employment. From 1933 until the finish of the war, this intelligent and energetic man was reduced to an observer, watching the gradual erosion of civil society around him, commencement with incredulity and then with horror. He concentrated his efforts on his immediate circle, urging Jewish friends to get out, and seeing off the Hitler Youth who came calling to forcibly recruit his sons.

Fest absorbed his father'southward scathing view of the regime, scratching caricatures of Hitler on to his schoolhouse desk-bound. At the meeting that confirmed his subsequent expulsion, Fest's father put his arms about him – a rare and bravely public evidence of approbation. His blessing was not easily won. Of Fest's chosen field, his father said the Tertiary Reich was "no more than a gutter subject area. Hitler's supporters came from the gutter and that's where they belonged. Historians similar myself were giving them a historical dignity to which they were non entitled".

Fest senior learnt of the developing Holocaust through friends, and his sense of impotence must have been intolerable; it certainly left its scars. When his sons entreated him to write about his experiences after the war, he responded: "I did non desire to talk about it then, and I do non want to now. It reminds me that in that location was absolutely cipher I could practice with my knowledge." While others accustomed requisitioned villas in leafy suburbs from the Allies, Fest senior refused. "For bounty, my father had just the knowledge of meeting his own rigorous principles."

Non Me is a serenity, proud, often painful, always articulate-eyed memoir. That it was a bestseller in Federal republic of germany is perhaps not surprising, but it surely deserves broad attention in the English-speaking world. It is illuminating of the man, of the times he lived through, and also of a rare kind of moral resolve, both sobering and inspiring.

(8) The Daily Telegraph (13th September, 2006)

Joachim Fest, who died on Mon aged 79, was the nearly celebrated historian and the well-nigh distinguished journalist of the post-war generation in Federal republic of germany.

For some 20 years, he was i of the publishers (i.east. editors) of Frg'south leading paper, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, responsible for its prestigious Feuilleton or culture section.

Considering he was a announcer rather than a scholar, Fest's popularity aroused the green-eyed of professorial rivals, none of whom could match the incisive elegance of his writing. Equally important was his flair for controversy. He was determined to prevent the wrong lessons being fatigued from the past past the Left-wing establishment that had dominated German intellectual life since the 1960s.

Conservative in politics and Catholic by upbringing, Fest stood out amongst his contemporaries for his rejection of the influence of the Marxist sociologists of the Frankfurt school on the historiography of the Third Reich. Fest saw the Nazi phenomenon not as a product of capitalism, just as a moral ending, made possible by the abdication of responsibility on the part of educated Germans.

Merely equally he despised economic reductionism, however, Fest fabricated it his life'due south work to bring the Nazis down to earth, to betrayal their personalities and deeds to dispassionate scrutiny.

It was his mission to intermission the taboo that surrounded any comparison of the Holocaust with the crimes of other totalitarian regimes. This denial of the uniquely wicked character of Nazi Germany earned Fest vitriolic hostility from some quarters, specially during the so-called Historikerstreit ("historians' dispute") of the late 1980s, which revolved effectually the allegation that he and other "revisionists" were seeking to play down the gravity of the Nazi genocide.

This was a grotesquely misplaced charge, only his own mental attitude to the Nazis was one of cool distaste rather than hatred. He believed that the High german obsession with the Nazi past had go an obstacle to the state's normal evolution, and the failure of reunification to heal the wounds.

Joachim Clemens Fest was born on Dec 8 1926 in Berlin. His father, Hans, was a schoolmaster. A devout Cosmic, he refused to join the Nazi party or to allow his children to join the Hitler Youth. His disobedience of the regime got him the sack; he was not fifty-fifty allowed to give individual tuition.

In his memoirs, which were in the process of newspaper serialisation at the fourth dimension of his death, Fest recalled a dramatic argument betwixt his parents about the ideals of joining the Nazi political party for the sake of survival. His father stubbornly refused to join, declaring: "It would change everything!" This biting experience, which left the family unit virtually destitute, showed young Joachim the truthful confront of the Third Reich. In 1944 he faced such a choice himself, when he decided to volunteer for the Wehrmacht in order to avert being conscripted into the Waffen-SS. His begetter, who had already lost one son, did not approve of his son volunteering for "Hitler's criminal war". Afterwards Hans Fest told him: "You weren't in the incorrect, just I was in the correct!"

After spending some months in a PoW camp in French republic, Fest returned to Federal republic of germany, and so went to report at the universities of Freiburg, Frankfurt and Berlin. In 1954 he was employed past the radio station RIAS-Berlin as head of contemporary history. In 1961 he joined North High german Dissemination (NDR) as editor-in-chief.

Fest had his first literary success in 1963 with The Face of the Tertiary Reich, one of the first general accounts of the period to appear in German. The book immediately established his reputation as a profound still readable historian.

In 1966 he was approached past the publisher Wolf Jobst Siedler to assist Albert Speer, then approaching the end of his xx-twelvemonth judgement at Spandau, in the writing of his memoirs. The result was Inside the Third Reich, Speer's memoirs, which caused a sensation when it appeared in 1969. It was rumoured that Fest had well-nigh ghosted the book, which was followed by Speer'due south Spandau Diaries, but he denied that his role had been more than that of an agent.Decades subsequently, after controversy near Speer was reignited by Gitta Sereny's 1996 volume, challenge that Speer had lied virtually his cognition of the Final Solution, Fest produced his ain biography in 1999. Speer: The Final Verdict, largely based on the notes Fest took of his conversations with his subject area, is likely to remain the definitive work.

In 1973 Hitler appeared to universal acclaim. It immediately replaced Alan Bullock'southward biography as the standard work and has retained its value even today, despite Sir Ian Kershaw.

Other major works included a controversial account of the July plot of 1944, which criticised the British for not taking the conspirators seriously, and Inside Hitler'southward Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich (2004). This brief but brilliant portrait of Hitler's demise served as the basis of the successful film Downfall.

Joachim Fest received many honours in Germany and elsewhere. He is survived by his married woman and iii children. He also had a shut friendship with the journalist Gina Thomas.

(nine) Jane Burgermeister, The Guardian (14th September, 2006)

The work of the German historian and editor Joachim Fest, who has died at the historic period of 79, was shaped till its end by Adolf Hitler'southward rising to ability during his childhood. Well-nigh notable among the several books Fest wrote on the Nazi era, from a conservative, Catholic perspective but with considerable journalistic flair, was an authoritative biography of the dictator. Though Fest frequently maintained that he would have been happier studying the Italian Renaissance, he felt compelled to confront the great issues of German language life that he had been launched into from the start - above all, that of private pick under a totalitarian regime.

His combination of strong narrative and psychological insight produced bestsellers, and Inside Hitler'southward Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich, published in 2004, provided the ground, along with the writings of Hitler'south secretary Traudl Junge, for the flick Der Untergang (Downfall) the same year.

Just concluding calendar month, Fest hit the headlines when he accused Noble prizewinner Günter Grass of double standards for criticising High german society for failing to deal adequately with its Nazi past while keeping hole-and-corner his own membership of the Waffen-SS. Inspired by his father Johannes's resistance to the Nazis, Fest became convinced that responsibility for the emergence of the Third Reich lay with the millions of Germans who actively supported or turned a blind eye to Hitler'south regime. Examination of the question will continue with the publication of Fest's own memoirs, Ich Nicht (Non Me) - his begetter's statement of defiance - subsequently this month.

The plight of the "little people" caught up in brutal events engineered by others was a primal feature of Fest's upbringing. He was built-in in Berlin, and in 1933 his father lost his job as a schoolteacher because he refused to bring together the Nazi party. At the historic period of 9, Joachim recalled hearing a row in which his mother pleaded with his male parent to go a party member, arguing that a fiddling hypocrisy was justified to ease the hardship the family unit was undergoing. "Everyone else might join, but not me... We are not petty people in such matters," Johannes, a devout Cosmic, had replied; Joachim after recalled seeing him come abode covered in blood later on fighting street battles with Nazi Dark-brown Shirts.

At his male parent's insistence, Fest did not join the Hitler Youth, but in 1944 volunteered for the army to avoid conscription into the Waffen-SS. Johannes maintained that "one does not volunteer for Hitler's criminal war" and that conscription was preferable; later spending time as a PoW in France, Joachim revisited the subject with his begetter: "You weren't incorrect," the older man allowed him, "But I was the ane who was right."

His father's integrity became the standard Fest used to measure out the psychological weakness and moral prevarications of his countrymen in a lifelong quest to explain how they could take descended into the madness of the Holocaust. His profiles of prominent Nazis in The Face of the Third Reich (1963), his first success and a groundbreaking work for that time, could have come up direct from the pages of Dostoevsky as Fest probes in scintillating fashion the dysfunctional psyches, personal ambitions, contradictions and self-serving delusions of the men who helped create the Third Reich, while showing how they embodied the attitudes of their classes. Hitler (1973) broke new basis past focusing on a psychological exploration of the Nazi leader who, Fest said, operated like "a reptile", exterior established moral norms.

Speer: the Terminal Verdict (1999), written after the emergence of new bear witness of Albert Speer'due south entanglement with the Nazi murder machine, is a masterly written report in the psychological mechanisms of guilt and concealment. Fest concluded that Speer, Hitler's master builder and later on armaments minister - who, similar his principal, saw himself as an creative person above all norms - did non accept the moral or religious standards needed to tell the deviation between practiced and evil, but was absorbed with technical questions of how to accomplish his aims. Speer had given his own business relationship, with Fest's assistance, in Inside the Third Reich (1970) and Spandau: the Secret Diaries (1976).

Later the war, Fest studied history, folklore, German language literature, art history and law at Freiburg, Frankfurt am Main and Berlin universities, and joined the youth arm of the conservative Christian Democratic Union. His showtime chore was in radio, equally head of contemporary history with RIAS Berlin (1954-61), after which he moved to telly as editor-in-main of the Norddeutscher Rundfunk. From 1973 to 1993, he was co-editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and the caput of its culture section.

In 1986, he approved the publication of an article by the revisionist historian Ernst Nolte, who compared the Holocaust with Stalin's mass murder, triggering a bitter argue about the treatment of the Nazi period past German historians. Afterward, Fest distanced himself from Nolte, but continued to defend Nolte'southward right to put forrad his views.

An outspoken individualist difficult to label, Fest accused moving picture-maker Rainer Werner Fassbinder of beingness anti-Nazi only out of conformity to leftwing ideology, but he was expert friends with Ulrike Meinhof, the Red Army Faction terrorist, later on recalling the heated political debates he had enjoyed with her at parties. The brilliant, lively, gracious Fest was a tireless critic of contemporary German language society, accusing it of failing to institute clearer values as a safeguard confronting the emergence of another Hitler.

(10) David Childs, The Independent (22nd September, 2006)

Joachim Clemens Fest, writer and historian: born Berlin 8 December 1926; married 1959 Ingrid Ascher (two sons); died Kronberg im Taunus, Germany eleven September 2006.

Although he wrote about many aspects of the Federal republic of germany of his childhood, Nazi Germany, Joachim Fest volition be best remembered for his biography of Adolf Hitler.

Controversially, he explained the rise of Hitler in the fearfulness of the German language center classes of Bolshevism, in the shape of the large High german Communist Party (KPD). Just, in many respects, Fest was trying to answer the question which troubled the thinking, caring members of his generation, sometimes chosen the "Hitler Youth generation" - "How did we, and our parents, become into that awful, diabolical mess, the Hitler mess?"

Born in 1926 in the pleasant Berlin suburb of Karlshorst, he attended grammer school at that place and after, afterwards being expelled for anti-Nazi remarks, in Freiburg im Breisgau. Yet, the 2nd World State of war caught up with him. The town was bombed past the Luftwaffe by mistake, and later, by the RAF. Fest was sent as a boy helper to an anti-shipping bombardment. When the war ended in 1945 he was serving as a soldier in the Luftwaffe. He was lucky to be a prisoner of the Usa Army and got early release. His begetter spent years in a Soviet labour camp.

Studies in law, history, fine art history, High german and sociology took him to Freiburg im Breisgau, Frankfurt am Master and Berlin. There, he worked for the much-admired American radio station RIAS, from 1954 to 1961, as editor in charge of contemporary history. He then served as editor-in-chief of television for Due north High german Radio, NDR, from 1963 to 1968. He resigned from NDR afterwards a disagreement....

Between 1973 and 1993, he edited the culture section of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. During his time at the newspaper, Fest became involved in the so-called "Historikerstreit" (controversy amidst historians) because he published an article by a young man historian, Ernst Nolte, "Vergangenheit, die nicht vergehen will" ("The By That Will Not Disappear") which brought criticism that it was "revisionist" in relation to Nazi Germany and the Holocaust.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

The Last Days of Adolf Hitler (Reply Commentary)

References

(one) David Childs, The Independent (22nd September, 2006)

(2) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a High german Childhood (2006) folio 17

(3) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

(iv) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a High german Babyhood (2006) page 46

(5) Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian (10th August, 2006)

(half dozen) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Babyhood (2006) page 86

(7) Jane Burgermeister, The Guardian (14th September, 2006)

(8) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 52

(9) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a High german Childhood (2006) folio 55

(ten) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th Oct, 2012)

(eleven) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Report in Tyranny (1962) pages 425-429

(12) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) folio 118

(13) James Taylor and Warren Shaw, Dictionary of the Third Reich (1987) page 67

(14) Reinhard Heydrich, instructions for measures confronting Jews (10th November, 1938)

(15) Joseph Goebbels, article in the Völkischer Beobachter (12th Nov, 1938)

(16) Erich Dressler, Nine Lives Under the Nazis (2011) folio 66

(17) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 123

(xviii) Joachim Fest, Non I: Memoirs of a German Babyhood (2006) page 125

(xix) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th October, 2012)

(xx) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) folio 140

(21) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German language Childhood (2006) page 174

(22) Joachim Fest, Non I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 177

(23) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) page 207

(24) School report of Joachim Fest (May, 1944)

(25) The Daily Telegraph (13th September, 2006)

(26) Joachim Fest, Non I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) pages 268-271

(27) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German Childhood (2006) pages 285

(28) Jane Burgermeister, The Guardian (14th September, 2006)

(29) David Childs, The Independent (22nd September, 2006)

(30) Neal Ascherson, London Review of Books (25th Oct, 2012)

(31) Jane Burgermeister, The Guardian (14th September, 2006)

(32) The Daily Telegraph (13th September, 2006)

(33) Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian (tenth August, 2006)

(34) Ernst Nolte, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (6th June, 1986)

(35) Joachim Fest, Not I: Memoirs of a German language Childhood (2006) page 388

(36) The Daily Telegraph (13th September, 2006)

(37) Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian (10th August, 2006)

Source: https://spartacus-educational.com/Joachim_Fest.htm

0 Response to "Joachim Fest Histler Book Proud to Be German Again"

Post a Comment